Text: Adel Kim

PORTRAIT IN CONTEXT. GENERAL OVERVIEW OF THE RUSSIAN ART RESIDENCIES IN 2021

Images: courtesy of Fabrika CCI, Garage MCA, CEC ArtsLink, Vyksa AiR, POLENOVO AiR

Before embarking on the journey of examining Russian residencies as part of the Reside/Sustain project, it is essential to look around and understand what we are about to deal with. Art residencies exist all over the world, but what is it like in Russia and what are the distinctive features of the local institutions? In this article, I describe the state of art residencies in Russia as of the beginning of 2021.

The current image of Russian residency organisation within a global context, does not yet seem to be fully formed. Despite the work by some theorists and practitioners that I will mention in this text, Russian residencies rarely appear on the international radar. For example, in an article for Reclaiming Time and Space (2019) titled Rooted and Slow Institutions Reside in Remote Places, Vytautas Michelkevicius mentions Russia as a "country without a residential culture" (Kokko, Elfving, Gielen, 2019, p.160). This might partly reflect international sentiments. Nevertheless, there are no other references to Russian residencies in this authoritative publication written in English.

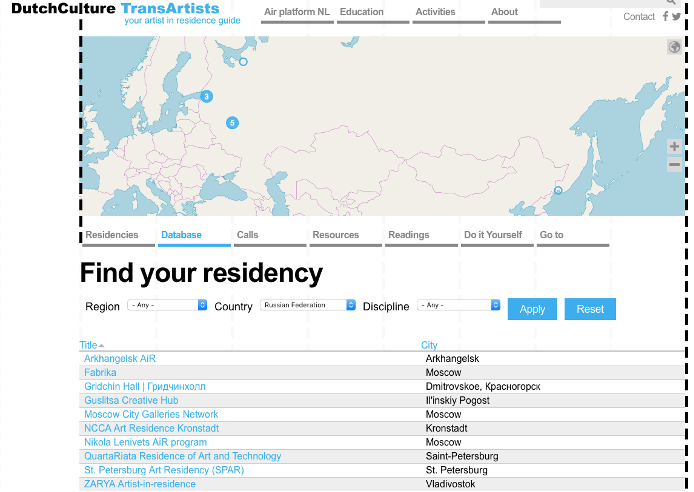

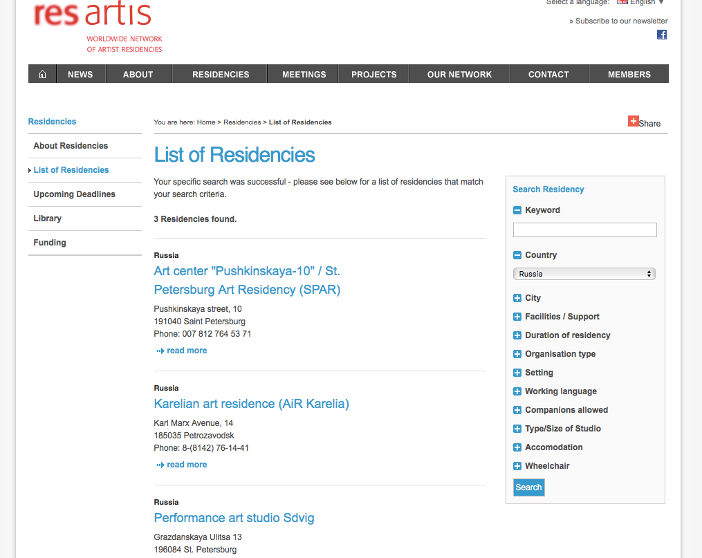

Key residency search engines provide limited information on Russian initiatives. In 2019, 11 Russian residencies could be found in the TransArtists database. There were 3 residencies mentioned in the Res Artis search engine that requires paid membership to be featured. Despite the continuous emergence of new players in addition to the creation of a professional association – the Association of Art Residences of Russia – in 2019, progress in visibility is rather slow.

Speakers from Russia rarely participate in professional conferences, such as those, for example, organised by Res Artis. According to network’s webpage, Russian speakers attended one conference in Lithuania that focused on the Baltics, Central Asia, Eastern Partnership countries, Nordics, and Russia, in 2014 (Anastasia Patsey from the Art Center Pushkinskaya 10, Elena Tsvetkova and Yulia Bardun from the Kaliningrad Center for Contemporary Art, and Victor Miziano who presented a report), as well as another one in Vienna in 2012 (Nikola-Lenivets, Georgy Nikich). The list ends there. Joint international projects with Russian residencies are implemented in cooperation with Russian representatives of international foundations and diplomatic missions, however, much less often in mutual exchange programmes with foreign residencies (such as Contact Zones Program of ZARYA AiR, later – Golubitskoye Art Foundation's, as well as residencies in the Open Studios of Winzavod).

Generally speaking, this is not too surprising – art residencies appeared in Russia later than in Europe, the USA, and some Asian countries: namely, in the late 2000s. Now, we are finally able to talk about the formation period of art residencies owing to professional comprehension of the first decade. Globally, there are not too many projects supporting systematic, international, and institutional exchange with Russia. Therefore, the field of art residencies in Russia, in general, remains terra incognita for many colleagues, even for those from neighbouring states.

It is important to mention that Russia has its own peculiarities when it comes to defining AiRs. So, when looking in Yandex and Google for an "art residency" in the Russian language, the search results include, among others, residential buildings and real estate, online platforms of creative professionals, short-term, one-time camps, different kinds of creative laboratories, discussion panels from the youth forum "Tavrida", and so on. These other sites almost outnumber the results for the actual art institutions. This makes it difficult to recognise art residencies as such, and can confuse potential residents, both foreign and local.

Published works and sources

There are several central texts for studying residencies in Russia and tracking change over the past decade. On the TransArtists's webpage, there is a short article devoted to the state of Russian residencies Tendencies and Intentions, written in 2012 by Georgi Nikich, cultural manager, lecturer at the Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences and initiator of residential projects. The same article under a different name ("Russian Art Residences: Trends and Intentions") that does not mention the author, was published in Russian, in the collection "Mutual AiR Impulse Russia" (Association of Cultural Managers. Mutual AiR Impulse Russia. TransArtists, ArtResideRUS, Nikola-Lenivets Park, Moscow – the Netherlands, 2012-2013). This collection was one of the outcomes of the cooperation between the Association of Cultural Managers, and representatives of art residencies from Russia along with the Dutch partners: Dutch Culture and TransArtists. The cooperation was envisioned as a long-term project and was supposed to promote the on-going exchange of knowledge and experience in the field of art residencies between the two countries. However, there are no further traces of this initiative after the mentioned publication.

In the article, Nikich draws attention to the fact that art residencies in Russia are an imported phenomenon which therefore has not yet been included in institutional systems and budgets. Leaving that aside, the format of art residencies is a bit challenging to characterise, mainly because they involve the stay and work of artists, but not the purposeful creation of any result. He writes: "The very presence of a creative person, their formation of connections to a place and people and their creation of an atmosphere that determines the possibilities for development are not sufficient motivation for possible "providers" of art residencies."

According to the author, the growing interest in the phenomenon of residencies, as well as the use of the term in Russia, is connected to the international symposium "Artists in residence. Culture? Tourism? Territorial development?" that took place in 2010. Years later, Nikich observes the presence of the two main residency models: an eventful residency which involves a purposeful invitation / creative work for an "occasion" (in other words, tied to some large-scale event), and a situational residency which includes "social interaction or work with environment, inter-professional or interdisciplinary activity".

Although the author, being rightly surprised, points out that art residencies can only be found in three cities in Russia (Moscow, St. Petersburg, Perm), the collection features 14 residential initiatives: Daniil Kharms Art Residency in Novosibirsk, National Centre for Contemporary Art’s branch in Nizhny Novgorod, National Centre for Contemporary Art’s residency in Saint Petersburg, project artHOME in Astrakhan, Kodirandu house in Karelia, Geese Fields centre in Karelia, Pasternak's house in Perm region, Perm Art Residency, residential programme Public Art museum PERMM in Perm, PROJECT_FABRИКА in Moscow, International Shiryaevo Biennale in Samara, Yasnaya Polyana in Krapivna, art residency programme of the 2nd Ural Industrial Biennale of Contemporary Art in Yekaterinburg, and art-park Nikola-Lenivets in the Kaluga region. Only three of them – the programmes of the Ural Industrial Biennale, Fabrika, and Perm Art Residency – are still active to this day. Nevertheless, the author predicts the imminent boom of art residencies in Russia. As of 2021, this forecast came true.

Another text on the topic of Russian residencies worth mentioning is the text "The General Mapping of Artistic Residences in Russia" written by the curator and researcher of the Association of Artistic Residencies of Russia's Zhenya Chaika, and commissioned by the Embassy of Sweden in Russia and Goethe Institute in Moscow.

In this article, Chaika claims that the format of art residencies was adopted from the existing practice in the other countries. She emphasises the fact that organisations, such as the Union of Artists that originated from the Soviet cultural system, do not participate in the creation of residencies conceptually or infrastructurally. Indeed, the so-called Houses of Artists and Writers, the creative dachas [author’s note: Dacha refers to a summer house, which have been very popular among the Soviet and, later, post-soviet citizens since the mid 20th century. Creative dachas (or "tvorcheskaya dacha", or "house of creativity" – "dom tvorchestva"), were organised by an official institution, such as the professional unions of artists or writers, where creative workers from all over the USSR could work, rest, and communicate with each other.] and other initiatives that were a part of the effective art production system of the USSR, functioned similarly to art residencies long before the term was coined. However, the way they operate now bears little resemblance to this former type of support.

Chaika states that residency organisers had different motivations for art residencies at different times. For example, at first they were driven by the availability of infrastructure, space for life and creativity (2006-2012). Later, the emergence of residencies was dictated by the needs of the specific territory (2012-2016), programme activities and international format (2016-2019). In 2017-2019, curated residencies were on the rise. Now, the main driving force behind the residencies are the country's largest art institutions that have finally become interested in this format (2019-2022).

The author emphasises that art residencies often act as an auxiliary tool for achieving external or internal goals; they are result-oriented, and often face difficulties in organisation processes due to resources, infrastructure, and staff. Chaika also outlines the legal complexities that art residencies face due to the fact that they are not fully recognised by the Ministry of Culture. These challenges include difficulties in concluding agreements with foreign citizens (in the case of working grant applicants), justifying working grants in general (typically, contracts with individuals imply a transfer of goods or services), combining residential and public space and, as a result, challenges with the temporary registration of foreign participants.

Now, 7 years after Nikich’s article was published, Chaika lists 38 residency programmes in Russia.

In 2019, when a lot of new programmes emerged, two specialised issues of "Iskusstvo" (ENG: Art) magazine were published: No. 3 (610) and No. 4 (611). They were dedicated to the phenomenon of art residencies and their historical background. The key publication, however, is an interview with 17 curators and the residency organisers of 17 Russian residencies. The interviews are available online, only in Russian.

Portrait of Russian residencies

Below, I provide statistical data that allows us to identify key aspects in the field of art residencies in Russia. This information comes from the open sources; AiR of Russia residency catalogue (available at the Association's webpage airofrussia.com, created by Anastasia Bogomolova and myself), as well as the websites and social media channels of these residencies. It is worth mentioning that the AiR of Russia catalogue is not exhaustive: several residencies that comply with the residency criteria did not wish to be included in the catalogue, so information about them is neither shared on the website nor included in the statistics provided.

On the other hand, the AiR of Russia database only includes residences that meet the formal requirements: as mentioned above, some organisations may hold the name, but not the essence of an art residency. At the moment, the criteria for being included in the residency catalogue are formulated as follows: “[…] projects or institutions that provide space, time, and resources for art and cultural professionals to work, in order to support their practice. We do not regard commercial organisations, hotels and hostels, creative youth camps, creative houses, incubators, accelerators, co-working spaces, etc. as art residencies.”

The database includes 30 art residencies:

1. Marin Dom

2. Polar Art Residence

3. Art-dacha Paytihatki

4. Vyksa Artist-in-Residence

5. Art Residences PENZA

6. FM-residency

7. Fabrika CCI Artist in Residence Program

8. Golubitskoe Art Residency

9. Garage Studios

10. New Stories of Yekaterinburg

11. CAMP AS ONE

12. Gridchinhall

13. ArtsLink Back Apartment Residency

14. AIR (Art.ITMO.Residency)

15. Dacha Ryabushinsky

16. Shishim Hill AiR

17. St. Petersburg Art Residency

18. Artist-in-Residence Program of the Ural Industrial Biennial of Contemporary Art

19. Studio 4413 residency

20. Art residence “Petrozavodsk”

21. Art Residence Nikola-Lenivets

22. POLENOVO A-I-R

23. Smirnov Sorokin Foundation

24. ART RESIDENCE SORTAVALA

25. Vorota

26. The museum residence ‘Artкommunalka. Erofeev and Others’

27. Kostomuksha

28. Winzavod Open Studios Residency

29. The Gogova Foundation Artists Residency

30. #VirtualSPAR

Information about the organisations

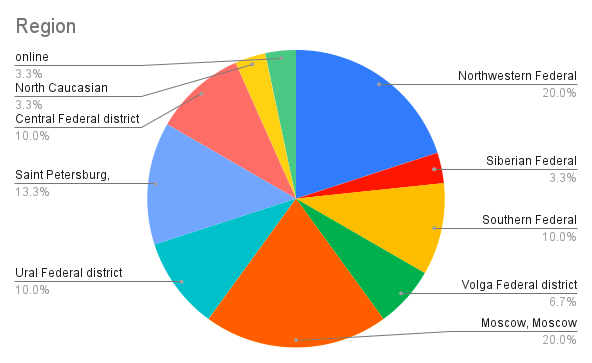

Six of the existing institutions are located in Moscow and the Moscow region. Six others – in the Northwestern federal district (Karelia, Kaliningrad, Murmansk, and Arkhangelsk regions). The third most popular region is St. Petersburg and the Leningrad region – four art residencies are based there. Three art residencies are located in the Central district (the Kaluga, Tver, and Tula regions), Ural (Ekaterinburg), and the Southern (Krasnodar Territory) federal districts. Two residencies are located in the Volga federal district (Nizhny Novgorod Region and Penza). Finally, one residency is based in the Siberian district (Norilsk) and one in the North Caucasian (Karachay-Cherkessia) federal district.

Despite art residencies being rather popular, the territory beyond Baikal, including Siberia and the Far East (about one third of the length of the country) offers no residencies at the moment. The ZARYA residency was formerly active in the East, however, it discontinued operations in 2020.

An updated map of Russian residencies is available on AiR of Russia's website.

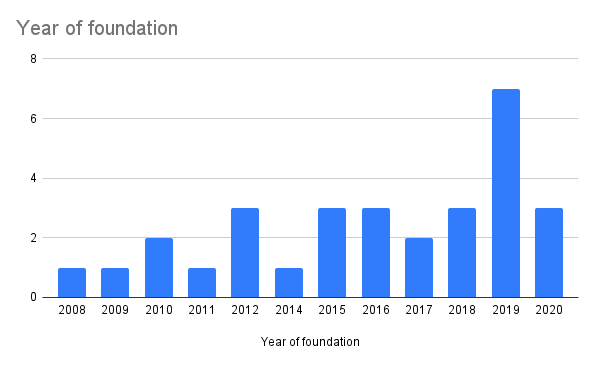

This diagram provides information on the number of residencies that were launched over the last 15 years. In 2008-2011, a maximum of one to two residencies opened each year, followed by three in 2012, 2015, 2016, and 2018. In 2019, we see a sudden surge with 7 new residencies. Despite the pandemic, 3 residencies opened in 2020. In general, one can observe growth, albeit unstable, in the number of residential programmes and institutions initiated. This indicates that in recent years, this format has become more common and this allows us to make assumptions about the continued development of this trend.

It is also important to note that the list of residencies includes only those initiatives and institutions that were in operation when this article was written. Other residencies that were shut down or put on hold are not mentioned here. These include the art residency of the National Center for Contemporary Art in Kronstadt, the art residencies of the Exhibition Halls of Moscow, the Mountain Art Residency “Colour Mountains”, “Odnushka”, QuartaRiata, ZARYA, and others.

In most cases, residencies are not independent organisations but rather programmes in institutions. Commonly, they are the programmes of private (9) or state (5) art institutions. However, they can also be artist-run organisations (3) or individual initiatives (3) (out of these three, two are the initiatives of professional gallerists). Non-profit organisations (3), universities (1), commercial organisations (1), government agencies not related to the field of culture (1), foreign arts foundations (1), charitable foundations (1), and public organisations (1) can also act as residency organisers.

Selection method

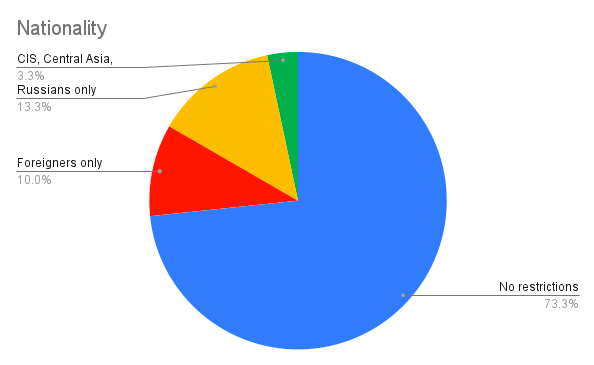

Most residencies tend to have no limitations regarding the nationality of the residency applicants. 22 art residencies are open to the passport holders of any state. However, four art residencies work exclusively with the residents of the Russian Federation. This is partly due to the peculiarities of the region: for example, to get to Norilsk, a citizen of a foreign country needs to obtain a special permit, and the participation in a residency programme is not normally a sufficient reason for this. Three of the residencies work exclusively with foreign citizens. Additionally, one of them offers accommodation for citizens of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the Middle East and Central Asia (the choice is mainly influenced by the geographical location of the residency which is in Karachay-Cherkessia).

Interestingly, residencies that offer paid accommodation (these are covered later in this text) focus mainly on foreign artists, although some of them are open to residents from all over the world.

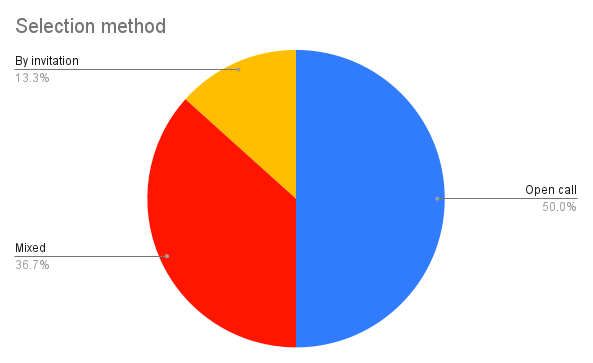

When it comes to the selection procedure, most art residencies (15) operate through open calls. Some (11) combine open calls and curatorial selections. Only four residencies work solely with residents invited by curators.

Living and working conditions

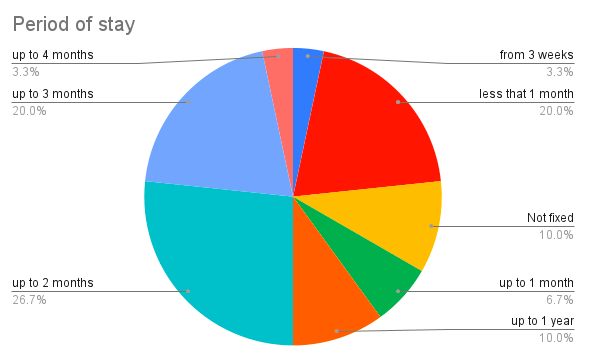

The majority of residencies provide short and intermediate term stays. The most common duration for a residency stay is either up to two (8) or three months (6). Six of the residencies offer their premises for less than a month. Durations are normally announced for a stay of "1-2 months", but artists know that this is often not the case and they can plan on shorter times instead.

Only one residency provides stays for up to four months, and three are ready to work with an artist for longer periods of up to 1 year.

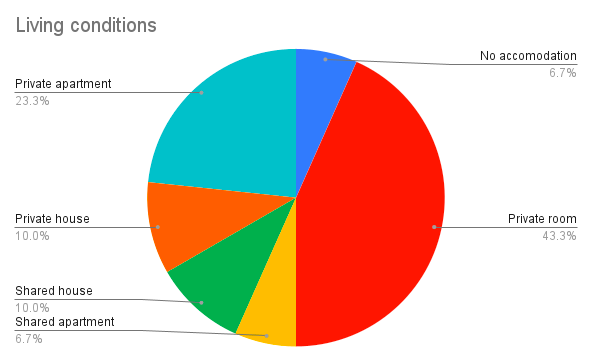

Residencies provide artists with a separate space to live. The most common options are either private rooms (13) or apartments (7). However, it might also be a house (3), a shared house (3), or a shared apartment (2). None of the residencies on this list offer shared rooms for the artists. In addition, two residencies do not provide accommodation (one of them is an online residency and the other one rents spaces according to its budget).

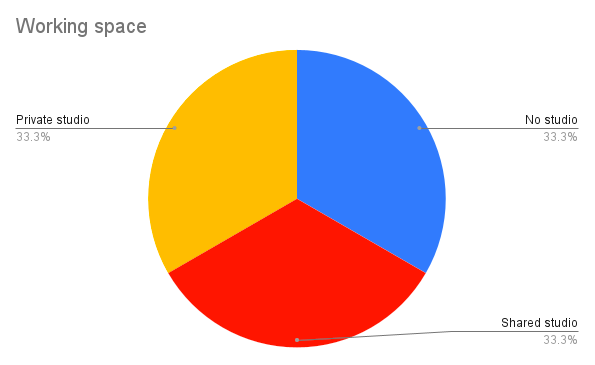

When it comes to working space,10 residencies provide the artists with personal studios, another 10 with shared workshops, and the last 10 do not have workspaces for residents.

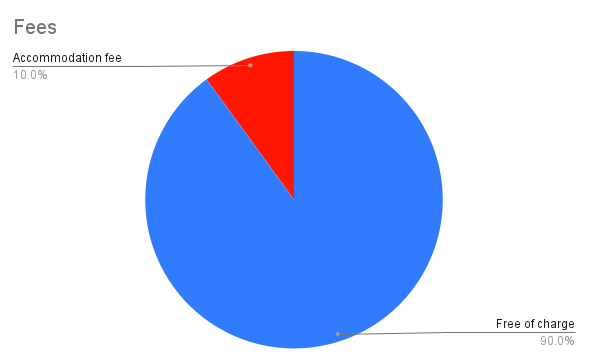

Most of the residencies are free for participants. However, three residencies charge from 3,000 rubles per week (Sortavala) to 30 euros per day (CCI Fabrika) for accommodation. These prices are significantly lower than rent on the market for short-term rental housing.

None of the respondents charge an application fee.

Support and requirements

All of the residencies support artists and their workflow to some extent according to the resources available. This is, in fact, their key responsibility. The respondents highlighted the following kinds of support:

Providing free accommodation – 25

Organising exhibitions – 22

Organising meetings with curators, critics, art professionals – 21

Providing materials for work – 19

Assisting – 18

Covering travel costs – 17

Providing tools for work – 17

Providing financial support – 13 (working grant – 7, per diem – 5, honorarium – 1)

Helping with applying for visa and/or travel grant – 13

Writing curatorial texts – 13

Helping with translation – 12

Including publications in the catalogue – 6

Offering free meals – 6

Other – 4

As the answers show, residencies see themselves above all as spaces ("places") – free accommodation is provided by the vast majority of the respondents. In addition, almost half of the residencies provide financial support for the artists in the form of a grant, per diem or honorarium. Since in the local contemporary art field grant programmes for contemporary artists are almost non-existent (with a few exceptions such as the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art's programmes and rare grants from the unions of creative workers), all of a sudden residencies have become an opportunity to maintain financial welfare. There was no direct correlation between the type of organisation (founder) and the working grant: they are provided by state, private, commercial, and public organisations.

Other forms of financial support include providing materials and tools for work (or covering their costs) which is a common practice for more than 50% of respondents. Over half of the residencies cover the artists' travel fees to and from the residency location, making it unnecessary for the residents to look for additional funding. Finally, six residencies provide meals which benefits participants significantly in terms of resources such as time and money.

Another type of support offered by the residencies is organisational. Some of them arrange meetings with curators and community representatives, provide practical assistance, translation services for foreign residents, and help them with applying for visas. Writing curatorial texts and publishing documents in the catalogues offered by some residencies, fall under this category. It is worth mentioning that 22 residencies assist artists with organising exhibitions. This can be viewed not only as support, but also as an obligation: it shows a tendency towards project-oriented models of residential stay.

The following were mentioned as residents' obligations:

Public meetings – 25

Presentation of results – 16

Exhibition – 15

Donation of artworks – 10

Open Studios – 9

Public access to the workshop – 8

Other – 6

None – 1

Most of the respondents (25) mention holding public meetings (lectures, workshops for adults or children, etc.) as obligations. In addition, some residencies arrange Open Studios (9), and others demand the artists' studios remain open to the public (8).

At least half of the residencies have their minds set on presenting the results in the form of exhibitions (15), while others are open to demonstrating the outcomes in a number of different ways (16). This demonstrates the desire of the residencies to get solid results from the artists' residency stays. It also indicates a willingness to shape the event programme of the institution at the expense of the residents who are not necessarily financially compensated for these events.

Asking for artworks, produced in the framework of the residency, to be donated is common for 10 residencies, i.e. one third of the respondents. This is a long-standing and very problematic practice reflecting the "barter approach" in working with artists: the contemporary art support system does indeed contribute to the artistic process, but also asks for a "token" in exchange for its work and generosity. This obligation is usually included in the residency announcements and the expectations from both sides are seemingly agreed upon by default. In practice, the scheme is not transparent: artwork is chosen by a curator, the number of works is not specified in advance, and the contract is either missing or signed ex post facto. Not to mention the ethical problems of such a practice. The study of forming private and institutional art collections with the resources of the residency organisations in Russia deserves its own article, so we will not go into details. It is, however, worth mentioning.

Other parameters

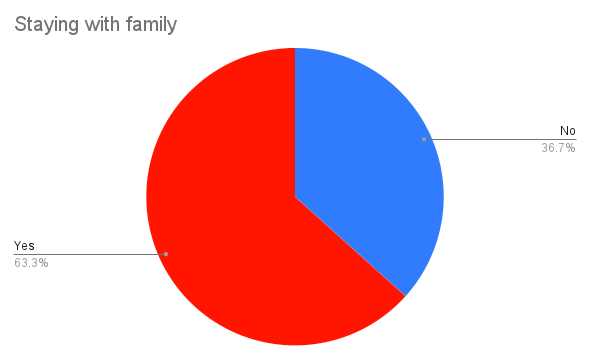

Most of the residencies (19), if necessary, are ready to accommodate the artists' family members. There is no information regarding additional opportunities and activities for them. Another 11 residencies can only accommodate the main resident.

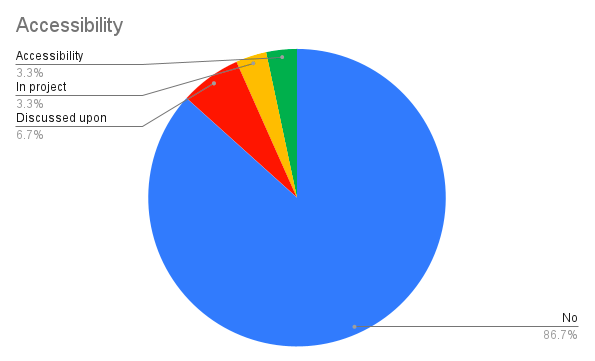

Accessibility, despite substantial presence in the local cultural environment, exists in only four residencies in one form or another. There was no talk whatsoever of specialised programmes. Residencies use ambiguous phrases such as "open to all artists", "we provide a personalised approach to each resident". There is an accessible (barrier-free) area in one of the residencies, and another one is currently being designed. However, the absence of physical barriers is not enough in and of itself, for a resident with limited mobility. So it seems that these measures are more likely provided for making the visitors’ visit more convenient.

The other 26 residencies have not yet addressed the topic of accessibility.

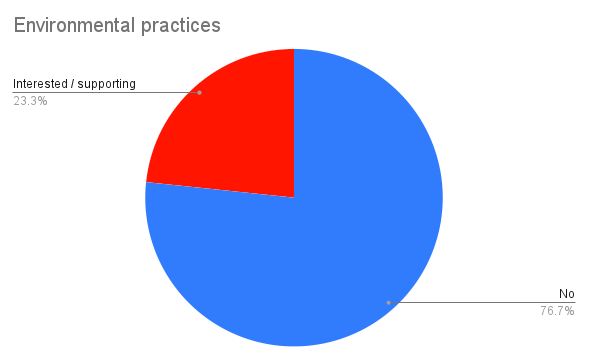

Environmental practices receive more attention from Russian residencies – seven respondents declared their interest or their specific undertaken actions. The following comments were received:

- "We elaborate on every project and try to create thought-out, long-lasting pieces using local materials";

- "The residency is environmentally conscious and this is reflected, not only in the methods of production and project presentations, but also in the way in which the manor house, free of any technological advancements, is used. Traditionally, the projects created here are site-specific: artists use local materials";

- "Participants' projects may focus on environmental sustainability. Even though there are no specific programmes within the residency, we welcome projects dealing with this topic";

- "We prioritise using natural materials";

- "Eco-tours".

Judging by the comments, institutions focus on motivating artists to work in an environmentally friendly way rather than changing their institutional activities and programmes. Many residencies suggest using materials found locally, natural materials, and found objects. At the same time, questions related to carbon emissions caused by travelling, reducing energy consumption, reusing materials in exhibitions and project activities remained unaddressed.

General conclusions

At the moment, the field of art residencies in Russia is definitely in a stage of active development. This statement is supported by the number of new residency institutions appearing annually. In conclusion, I can list the following characteristic features of Russian residences:

- decentralisation, local orientation. Despite the large number of residencies in capital cities, most of them are located outside of Moscow, Saint Petersburg, and the surrounding regions. Residencies often use phrases such as "local context", "local identity", and "local community" and try to collaborate with the local scene.

- the recent annual increase in the number of operating residencies makes it possible to predict the continuation of this trend, regardless of external obstacles, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

- existence within private and public art institutions. Residencies are mostly programmes within larger specialised organisations.

- short and intermediate-terms of stay for artists. The majority of residencies offer 1-2, sometimes 3 months residency stays.

- project/event orientation. In most of the cases, residencies require presenting the results of the residency stay (as a presentation, or exhibition). Thus, the residents also play a role in maintaining the activities of the institution.

- providing organisational assistance alongside covering some of the costs. Not all residencies have the resources to fully support artists, but strive to do so.

- as for environmental practices, at the moment these are underdeveloped. The few existing residencies which promote environmental practices shift the responsibility from the institution to the resident.

The features outlined above are reliant on the peculiarities of the art system and current state policy in the cultural field.